Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave Summary

Frederick Douglass • Autobiography, slave narrative

Summary

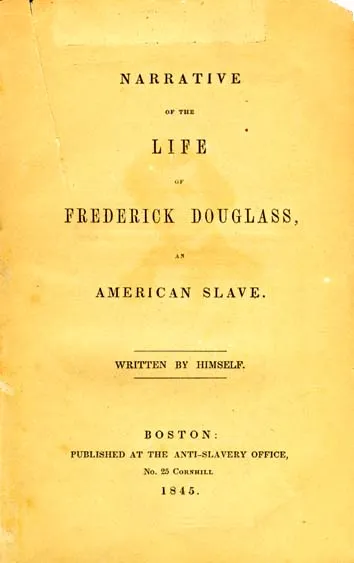

Published in 1845, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave is a groundbreaking autobiography by Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved African American who became a leading abolitionist, writer, and statesman. Douglass begins his story by recounting his birth and early experiences with slavery, emphasizing the uncertainty of his origins. The work serves as both a powerful personal memoir and a sharp political weapon against slavery. Douglass recounts his early life in Tuckahoe, Maryland, where he was born into slavery and deprived of basic identity—he never knew his exact date of birth or the identity of his father, and was separated from his mother, Harriet Bailey, at birth. His early age is marked by cruelty, hunger, and systematic dehumanization, illustrating the impact of slavery from childhood. The plantation where he lived included the Great House Farm, a symbol of wealth and authority on Colonel Lloyd's property, highlighting the stark contrast between the slaveholder’s opulence and the suffering of the enslaved. Douglass details the hardships he endured under various slaveholders, providing a vivid account of the brutality and neglect that defined his formative years.

Sent to Baltimore, Douglass experiences a turning point when Hugh's wife, Sophia Auld, initially shows him kindness by teaching him the alphabet, but she later transforms under the corrupting influence of slavery. Despite this, Douglass continues to pursue self-education, learning to read and write in secret and eventually acquiring the trade of ship caulking in Baltimore. During this time, he works under William Gardner, a shipbuilder, and faces racial tensions and challenges in the shipyard. His growing awareness of justice and human rights deepens as he reads works like The Columbian Orator.

Douglass’s time on different farms exposes him to various slaveholders, including William Freeland, or Freeland, who is noted for his relative fairness compared to others. While at Freeland's, Douglass plans an escape with fellow enslaved people, striving to become his own master. Under Edward Covey, Douglass faces brutal treatment and a lack of anyone to protect him from abuse, but he ultimately resists and regains his sense of dignity and self-worth.

Eventually, Douglass escapes to the North with the help of supporters like Nathan Johnson, who provides financial assistance and moral support after Douglass’s arrival. He settles in New Bedford, Massachusetts—a prosperous, free city often referred to as Bedford—where he and his wife Anna Murray begin a new life. Their marriage and new start are closely tied to the escape plans formed while at Freeland's farm.

In Massachusetts, Douglass becomes active in the abolition movement, attending an anti slavery convention and drawing inspiration from abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison. He is influenced by abolitionist newspapers, especially The Liberator, which motivates him to become an anti-slavery speaker and advocate for emancipation.

Douglass’s narrative, also known as Frederick Douglass's Narrative or Douglass's autobiography, is an influential work that provides a firsthand account of his experiences. His autobiographies serve as powerful testimony, documenting the realities of slavery and the importance of personal agency. The account of his life, along with those of other former slaves, played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and advancing the abolitionist cause.

The abolition movement, fueled by abolitionist newspapers and the efforts of activists, gained momentum leading up to the Civil War, the conflict that ultimately ended slavery in the United States. Douglass’s story, and those of other former slaves, established them as credible witnesses whose narratives helped sway public opinion and promote emancipation.

Douglass continues to expand on themes of resistance, education, and moral critique throughout his writings, reinforcing the ongoing impact of his life and work. Frederick Douglass's relationships, experiences, and legacy remain central to understanding the struggle for freedom and equality in American history.

Characters

Frederick Douglass is the central figure and narrator, embodying the transformation from enslaved victim to empowered intellectual and activist. His journey reflects both personal resilience and the universal struggle for freedom. Douglass’s birth is marked by uncertainty about his father, a fact that deeply impacts his sense of identity and highlights the generational trauma of slavery.

Sophia Auld, his master’s wife in Baltimore, represents the corrupting influence of slavery—initially kind and nurturing, she becomes cruel once forbidden from teaching Douglass, showing how the institution dehumanizes enslavers as well as the enslaved.

Hugh Auld, Sophia’s husband, symbolizes the systemic fear of educated slaves; his command to stop Douglass’s lessons reveals how literacy threatened the foundations of slavery.

Edward Covey, known as “the slave breaker,” personifies the brutality of the system. His defeat by Douglass is one of the book’s most powerful moments of resistance.

Thomas Auld exemplifies religious hypocrisy—professing Christian values while committing acts of cruelty. Through him, Douglass exposes how religion was often used to justify oppression.

William Freeland is described as a relatively fair master under whom Douglass lived for a time. Freeland’s farm is notable for Douglass’s efforts to educate other enslaved people and for planning an escape.

William Gardner is a Baltimore shipbuilder who trained Douglass in ship caulking. Gardner’s shipyard was marked by racial tensions and the pressures of meeting deadlines.

Secondary figures such as Harriet Bailey (Douglass’s mother) and Anna Murray (his wife) contribute emotional and moral grounding, representing love, sacrifice, and the hope of liberation.

Women in the Life of Frederick Douglass

The women in Frederick Douglass’s life played pivotal roles in shaping his journey from bondage to freedom, leaving indelible marks on his character and worldview. From his earliest days as an enslaved person in Maryland, Douglass’s experiences with women—both enslaved and free, nurturing and oppressive—deeply influenced his understanding of family, humanity, and the brutal realities of slavery.

His mother, Harriet Bailey, was separated from Douglass shortly after his birth, a common practice among slaveholders to weaken family bonds. Despite the forced distance, Harriet made nighttime journeys to visit her son, demonstrating a mother’s love and sacrifice even under the harshest conditions. Her early death left Douglass with only faint memories, but her devotion lingered as a source of inspiration throughout his life.

After his mother’s separation, Douglass was raised by his grandmother, Betsey Bailey, on Captain Anthony’s plantation. Betsey provided care and stability during Douglass’s early childhood, connecting him to his roots and offering a rare sense of familial warmth in a world defined by cruelty and uncertainty.

Sophia Auld, the wife of Hugh Auld in Baltimore, stands out as a complex figure in Douglass’s narrative. Initially, Sophia’s kindness and willingness to teach Douglass the alphabet opened a door to education and hope. However, as she adapted to the expectations of slave owners, Sophia’s demeanor hardened, and she became an example of how the institution of slavery could corrupt even those with compassionate instincts.

Aunt Hester, Douglass’s aunt, is remembered for her beauty and dignity, but also for the suffering she endured at the hands of Captain Anthony. Her brutal whippings were among Douglass’s earliest and most traumatic memories, exposing him to the violence and vulnerability faced by enslaved women.

Anna Murray, a free Black woman from Baltimore, played a crucial role in Douglass’s escape to freedom. Her support and partnership were instrumental as Douglass made his way to New York, where they married and began a new life together in Massachusetts. Anna’s courage and commitment provided Douglass with the stability and encouragement he needed to pursue his work as an abolitionist and writer.

Lucretia Auld, Captain Anthony’s daughter and wife of Thomas Auld, inherited Douglass as part of her father’s estate. Her actions reflected the complicated roles women held within slaveholding families—sometimes offering small kindnesses, but ultimately upholding the system of slavery.

Through these women—Harriet and Betsey Bailey, Sophia and Lucretia Auld, Aunt Hester, and Anna Murray—Douglass’s narrative reveals the profound impact of female figures on his life. Their stories, woven throughout his autobiography, highlight both the resilience of the human spirit and the pervasive reach of slavery’s cruelty. Each woman, in her own way, shaped Douglass’s path from enslaved child to free man and influential abolitionist, underscoring the interconnectedness of personal relationships and the broader struggle for emancipation.

Analysis

Douglass’s Narrative stands as a foundational text in abolitionist literature, serving both as a personal testimony and a political manifesto. As one of the most influential autobiographies of the nineteenth century, Douglass's autobiography provides an authentic account of his life as a slave and his journey to freedom. Through vivid storytelling and moral clarity, he dismantles the ideological machinery that sustains slavery. Literacy, in his experience, becomes a form of rebellion—an intellectual weapon that allows him to articulate his humanity and inspire others to do the same. Douglass details his confrontation with Covey, which symbolizes the reclaiming of his manhood and autonomy, illustrating that true freedom begins within the mind.

The text also critiques organized religion’s complicity in slavery: Douglass draws a sharp line between the “Christianity of Christ,” rooted in compassion, and the “Christianity of the South,” steeped in violence and hypocrisy. On a structural level, Douglass's narrative bridges personal and collective struggle—its emotional force invites empathy, while its reasoned arguments appeal to moral and political conscience. The recurring themes of dehumanization, resistance, and the redemptive power of education underscore the broader message: that freedom is not merely the absence of chains, but the awakening of selfhood.

As part of the broader abolition movement, Frederick Douglass's narrative and those of other former slaves played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and mobilizing abolitionists in both the United States and Europe. These firsthand accounts provided irrefutable evidence of slavery’s horrors, helping to galvanize support that would ultimately culminate in the Civil War and the end of slavery. Douglass continues to expand on these themes throughout his work, reinforcing the importance of personal testimony in the fight for justice and equality.

Conclusion

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave remains one of the most influential works in American literature and history. It is a profound exploration of how knowledge, courage, and moral conviction can overcome even the most oppressive systems. Beyond documenting the cruelty of slavery, Douglass’s autobiography offers an enduring message about the transformative power of education and the resilience of the human spirit. His life story bridges the personal and the political—showing that emancipation begins with self-awareness and culminates in collective struggle. More than a memoir, it is a blueprint for liberation and a timeless reminder of the ongoing fight for justice and equality.

Level up your reading with Peech

Boost your productivity and absorb knowledge faster than ever.

Start now